The actor, Kevin Kennedy, takes the lead role in ‘Cinderella’, this year’s pantomime at The Empire Theatre in Consett, a small town in the Northeast of England. Best known for playing Curly Watts, the politically savvy binman on the long-running British soap series, Coronation Street, Kennedy also flirted with the underground music scene in Manchester during the late 1970s and early 80s.

As a pupil at St Augustine’s school in Wythenshawe – and then known Kevin Williams – he was a member of a fledgling band called The Paris Valentinos alongside Johnny Marr [then John Maher] and Andy Rourke, both of whom would later feature in The Smiths. As Kennedy told the writer and biographer, Johnny Rogan: ‘These were the playground years. Instead of having a gang, we had a band’.

At the same time in a hamlet called Witton Gilbert, ten miles from Consett and twenty from Newcastle, another young man of Irish lineage, Paddy McAloon, was assembling a guitar-led outfit of his own: Prefab Sprout. With his brother, Martin McAloon, on bass guitar and a school-friend, Michael Salmon, on drums, this group was also throwing early shapes, their material drawn around studied guitar work outs and decorated by the soft magic in Paddy’s voice.

From inside a local garage run by the McAloon’s’ father, a couple of crudely captured rehearsal tapes from the time suggest a semi-formed young band still growing into its body.

Prefab Sprout certainly didn’t arrive into the world ready to spring with a quickfire debut album and an obvious pathway to glory: their story is a bit more complicated than that. For a comprehensive telling, John Birch’s book, ‘Prefab Sprout: The Early Years‘, is a good a start as any.

Paddy once told a television interviewer that he wrote a dozen new songs a year: many of these have been re-interpreted, revised, re-visited and re-shaped over the decades and, in keeping with much of the mythology that now surrounds Prefab Sprout, many more are unlikely to ever see the light of day.

Now in his late 60s, he’s now based on the outskirts of Consett from where he’ll host the odd interviewer and, presumably, continues to write and record. His approach to his work is no doubt determined now by issues with both his hearing and his sight. Is he still writing a dozen new cuts every year? Who knows?

What we do know is that he’s certainly not as reclusive a figure as popular legend implies. From the odd snippet posted by fans on social media, he’s occasionally spotted out and about, a conspicuous, eminently approachable and thoroughly self-deprecating character. In his long grey hair and matching beard, trilby hat and cane, Paddy is arguably more recognisable now than he ever was when Prefab Sprout were cracking out middlingly successful pop singles during the late 1980s and early 90s.

It’s just that we don’t see – or hear – an awful lot of him. The last Prefab Sprout album, ‘Crimson Red’, was released over a decade ago and the band’s public face has, over the last eighteen months, been assumed by Paddy’s brother, Martin. Armed with an impressive battery of guitars, he’s done a long series of live solo shows in Britain and Ireland, pulling exclusively from the wide, varied – and difficult to play – Prefab Sprout canon.

Which is what bringing me to Consett. I was half-hoping, as I boarded a bus in Newcastle for the hour-long trip up into the belly of County Durham, that if I hung around long enough, I’d maybe catch sight of Paddy, out and about, weekending. That, in a bakery or a shop selling pens and ink, the word might become flesh and briefly dwell among us. Small re-assurance in a world that could do with it.

On the bus ride up into the hills, through Rowlands Gill and into the woody uplands that birthed the great songwriter’s songwriter, I look out over a manky mid-morning. How often did the emerging Prefab Sprout themselves make this haul down into the mouth of the Tyne? Down to the recently closed JG Windows music shop in the city’s Central Arcade? To meetings with its record company on Saint Thomas Street? And with what kind of hope, exactly, in their hearts?

And it’s a real climb too, up into Andromeda Heights, up past a slew of quaintly named stop-offs – Lintzford, Derwent Oak Farm – all speckled with lichen, algae and moss, their formidable old stone houses dominating the canvas. Our last stop before Consett is at Genesis Way, a reference that isn’t lost on me. Prefab Sprout’s work is shaped as keenly by the messages in the Old Testament as it is by albums like ‘From Genesis to Revelation’ and ‘The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway’ and I take that as an omen.

Like numerous similarly sized towns across Britain and Ireland, Consett has had the gut ripped from it by the arrival of the ubiquitous retail park on its surrounds. The town centre is grim enough and, on a drizzly morning in November, a Saturday market on one of the pedestrian streets selling sliders, vapes and knock-off football tops is its only concession to the vaguely glamourous or mildly contemporary. The real action is happening in the retail park.

Over the years, Paddy has rejected numerous offers to make radio and television documentaries about his work: I’ve personally sent at least two respected producers – and fans – in his direction, but to no avail. Colleagues in the U.K. tell similar stories. Paddy emerges only when he needs to and engages with the broader media only when he has a record to sell and a new song to sing. And even at that these engagements tend to be limited to a small coterie of trusted confidantes.

I asked after him – and Prefab Sprout – in a couple of the units in a shopping arcade in Consett, in a small café on the main drag and in a couple of pubs doing decent Saturday lunchtime trade. Back down the road, Newcastle United are taking on Arsenal in a Premier League game at Saint James’s Park and the boozers here that are carrying the live coverage have the punters hypnotised. Isak scores and its 1-0.

No one has the faintest idea who or what I’m on about. Not only that but, around the town centre, there’s not a single suggestion anywhere that raw genius often walks among it. The closest I get to Paddy is when I turn onto a side street and find Saint Patrick’s Catholic church. I complete a couple of laps, fuel up, keep my eyes peeled and even hit the retail park. No dice.

Ten miles from Newcastle, Sunderland is still best-known in Ireland for football. Roy Keane once managed the local club – which was fronted by another former Irish international player, Niall Quinn – and that’s the subject of an excellent Netflix series, ‘Sunderland ‘til I Die’. By a distance the best of several football-club based observational documentary strands that have emerged in its wake.

A local Metro service connects it with Newcastle and runs all the way out towards the beaches and boats at South and North Shields. From Prefab Sprout’s ‘Protest Songs’ elpee, ‘‘til The Cows Come Home’ references the demise of traditional industry and the abandoned docks around these parts, where ‘even the fishes are thin’.

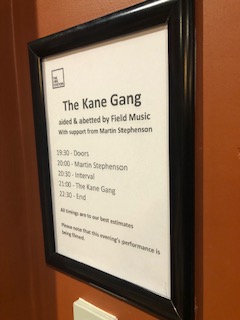

The Kane Gang, who formed just outside of Sunderland in the early 1980s, were label-mates of Prefab Sprout at Kitchenware Records, a local independent imprint run by Keith Armstrong, Phil Mitchell, and Paul Ludford. Having been a dormant concern for decades, the band is marking the fortieth anniversary of the release of its debut album for the label, ‘The Bad and Lowdown World of The Kane Gang’ with a rare live show in its hometown. And I’ve swung by for a nose.

With its three original members still in situ – vocalists Martin Brammer and Paul Woods and guitarist David Brewis – there’s a sense, as there tends to be with many of these reunions, that the band has unfinished business. ‘Aided and abetted’ by another formidable local troupe, the excellent Field Music, I’m not sure that The Kane Gang get the credit they’re due – not even in their own back yard – for the scale of their achievement. You’d wonder if that – and the fact that they’re simply just able to do so – is driving them?

But what was that achievement, exactly? Well, by enjoying moderate commercial success and decent notices with a considered, soul-tinged sound – and by sticking to their guns throughout – they also laid the ground on which a subsequent generation could kick on. Sunderland is a far better looking, better sounding and artsier consideration now than it was when I first encountered it in the early 1990s. Tonight’s venue – the impressive Fire Station – is a physical testament to that. And although The Kang Gang aren’t responsible for that, they’re certainly among those who, way back, set a ball or two rolling to get the town to here. A point that isn’t lost, I suspect, on Field Music, whose tentacles extend wide and deep into music and the arts in these parts.

Another local – Martin Stephenson – also sat in that class. Originally backed by The Daintees, he was another from the vaunted Kitchenware roster who, on ‘Boat to Bolivia’ and its immediate follow-ups, ‘Gladsome, Humour and Blue’ and ‘Salutation Road’, briefly scaled the critical heights during the mid and late 1980s.

His work has forever been rooted in the minutiae of the local and, in his reflections on the area that made him, is as sharp an observer now as he was when he was in his commercial pomp. A fine chronicler of the everyday North of England humdrum – and a captivating and humble story-teller – Martin is a regular visitor to Ireland and features in more detail in a previous piece here.

A welcome addition to the undercard, he opens proceedings with a stellar thirty-minute turn: sober for decades, he’s far more than a simple warm-up. Like a best man’s speech at a rascal’s wedding, his short set pulls everyone into his embrace and sets the rest of the night up for the headliners.

For good measure, he references Connolly’s of Leap, the eminent West Cork venue and bar which, under the stewardship of Paddy McNicholl during the early 1990s, became an essential stop on the Irish live circuit and an honours-level road test for any performer with even moderate aspirations. Describing the location and the unique stature of the venue to the audience, he refers to the main road out of Cork city and into the west, before playing ‘Long Forgotten’, one of the cuts from his mammoth 2002 elpee, ‘Collective Force’. A song, he says, he wrote in the venue as he looked out at towards the bridge into Union Hall.

By now I’ve struck up a conversation with another traveller: with his wife, brother and sister-in-law, he’s made the eighty-mile trip up from Scarborough, a seaside town in Yorkshire. We talk briefly about the quality of the venue and, after he queries my accent, about the distances we’ve both come. Unprompted, he tells me that Prefab Sprout’s ‘Steve McQueen’ is his favourite ever album and that it may, indeed, be the greatest record of all time.

In fact, such is his love for it that, in the months after its release in 1985, he hand-built a motorbike from spare parts in the exact likeness of the one straddled by Paddy and Wendy Smith on the sleeve. And he has the photographs on his phone to prove as much to me. Like the record that inspired it, he still takes it for the odd spin and it’s as roadworthy as anything.

By the time The Kane Gang hit their straps – propelled powerfully on bass and drums by Field Music – a couple of things are apparent. In as much as this is an anniversary celebration of a quality pop group, for many in the sold-out crowd, the night is also a nod to Kitchenware Records.

Apart from The Kane Gang, Prefab Sprout and Martin Stephenson, Kitchenware was also home to Hurrah, Cathal Coughlan, Editors and others. But it’s easy to lose track of these things over time and I was only reminded of just how formidable its back catalogue is after I recently re-immersed myself in it.

The Kane Gang go about their task with real gusto. Their set is peppered with the best of their two-album catalogue and all their best-known cuts are present and correct. Those twin vocalists are in fine fettle while, behind them, David Brewis – once cited by Paddy McAloon among the best producers he’s ever worked with – effortlessly pieces it all together. Like many of the great musicians, you’d only ever notice him if he wasn’t there.

An hour in, Brammer recalls travelling to a local music festival with his bandmate over forty years ago. The Kane Gang was in its infancy and dripping with the sort of confidence beloved of most young bands, a trait that’s only really tested outside of the safety of the rehearsal room. At that festival, another callow local outfit called Prefab Sprout played a stunning set that put manners on Brammer and Brewis and rocked them back on their heels.

And this is Martin McAloon’s cue to join the jamboree where, with that now familiar guitar, he leads the cast through a crude version of the Prefab Sprout masterpiece, ‘When Love Breaks Down’, and a muscular version of The Kane Gang’s ‘Smalltown Creed’. The significance of The Kane Gang, Field Music and Martin McAloon sharing the same stage and performing two powerful, locally sourced cuts, is a sight and a sound to behold.

We make the point consistently here about the thin line that often separates nostalgia from history: where does one end and the other begin? About the harm that the fog of one can have on the factual clarity of the other. But it’s no harm either to remind ourselves of where we’ve come from so to understand exactly how we’ve made it to where we are. And if that starts in Consett on a dismal Saturday in November, then so be it.

Leave a comment