Disco, diversity and Dubonnet. A special guest post by our own man in the sharp white suit, David Heffernan, on a lost world, new horizons, U2 and dancing delights in 1970s Ireland.

The ten years between 1969 and 1979 – from when the Gay and Civil Rights movements emerged in the United States until the Disco Sucks mob burned disco records in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, were a time in popular culture that regularly tends to get over-looked. But for most of that decade, the disco sounds – and their attendant lifestyle – were phenomenally popular and ubiquitous, laying the groundwork for nearly all modern music.

Disco originated in New York, in clubs and at house parties. Out of necessity, people from gay, trans, and marginalised communities – predominantly black and Latino – lost themselves in pulsating rhythms. DJs initially spun music from Africa, performed by relatively unknown artists like Manu Dibango and Fela Kuti and, in the process, helped create the genre we now call ‘disco’.

Over time, many acts emerged from labels devoted to disco, usually featuring US and Cuban music. Most notably among them, the socially conscious output – with lavish string arrangements – of Philadelphia International Records, headed up by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, Billy Paul and MFSB. The brainchild of local musicians and producers, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, the label’s influence and impact was celebrated by leading stars, among them Elton John, who dedicated his 1975 chart-topping ‘Philadelphia Freedom’ single to the label. So too David Bowie, who recorded ‘Young Americans’ in Sigma Sounds, Philadelphia International’s house studio.

Miami-based TK Records served up Latin-infused ‘pop’ arrangements and generated considerable commercial success with George McCrae and KC and the Sunshine Band. Mainstream labels responded quickly, signing BT Express, Brass Construction and Kool and the Gang, eager purveyors of urban funk, alongside established R&B singers Gloria Gaynor, Thelma Houston and Patti LaBelle. Casablanca Records, the most notorious, flourishing independent label of the time, brought the phenomenal Donna Summer – via German producer Georgio Moroder- to a global audience.

Established chart-toppers like James Brown, Diana Ross, Isaac Hayes, Marvin Gaye, Earth, Wind and Fire and Michael Jackson all enjoyed massive success on the dancefloor. And, lest we forget, the likes of Blondie, ELO, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd and Rod Stewart also tapped into disco and what was, for a time, an unrelenting dominance of mainstream culture.

This period of frantic activity in the music industry was triggered by the release, in 1974, of Hue’s Corporation’s infectious, easy-going ‘Rock the Boat’ single. Alongside Barry White’s effusive, propulsive ‘Love Theme’ – issued the same year – disco was suddenly in the mainstream, Billboard magazine proclaiming that it was ‘Rapidly becoming the universal pop music’.

Years before the Bee Gees released ‘You Should Be Dancing’, hordes from New York to Newtownmountkennedy, were already pumping it out on the dancefloor. But after 1977, and following the enormous success of the film, Saturday Night Fever, and the opening of super-clubs like Studio 54, disco came to represent the nadir of bloated consumerism. By then it had become a tacky cultural artifact, a pariah to many music fans. According to the New York Times, [disco] was ‘without substance, subtlety or more than surface sexuality’.

But this was precisely the point: disco was never about lofty aspirations. It was about coming together to dance, a highly social escapism. For many who were there at the time – and countless others who still love to just dance and listen to dance music – it lives on and remains a desirable way to spend a good night out.

Until the late 1960s, Dublin’s O’Connell Street and the side streets off of it, was the pre-eminent destination for those seeking entertainment in the capital, a hub of nightlife for most of the city’s denizens. Men and women dressed up and socialised in its many cinemas, cafes and dancefloors. The discos that sprung up there in the early to mid-’70s did so during a period of urban decline: in Dublin’s case, this spelt the last hurrah of the north city centre. The locus of entertainment began to move south of the River Liffey, where it largely remains today.

Sackville Place is a small side street east of the capital’s main thoroughfare. Across the road from the GPO, its short block of buildings abuts Marlborough Street, where three men were killed in one of the four bomb attacks that took place in Dublin between late 1972 and early 1973. Around the corner is the home of the national theatre on Abbey Street.

Sackville Place once housed a basement nightclub, the far less salubrious Club-A-Go-Go, which was frequented chiefly by musicians and other ne’er-do-wells during its 1960s heyday. In the early 70s, it was re-named, with what I suspect was unintentioned irony, as Lord John. This seems to have been a grandiose statement of intent by the club’s owner, a former cattle dealer from the midlands, John Ryan.

I knew Ryan’s family well. Our families were neighbours and his eldest daughter, Elizabeth, was a girlfriend of mine when we were teenagers.

Another relationship of mine – with disco music – began when I became a weekend DJ while still in secondary school. The music was a far cry from that of Frank Zappa or Lou Reed, to which I was listening intently at the time. But African American music had started to impact on me too, beginning with Aretha Franklin’s sublime recording of ‘Spanish Harlem’ and Otis Redding’s achingly tender ‘These Arms of Mine’. This continues to the present day.

John Ryan realised that Dublin city was changing and that its people were becoming more aspirational: an emerging generation was looking for a new, more urbane identity. Conscious of the history of his surrounds on Sackville Place and its environs, Ryan believed that a more cosmopolitan, sophisticated future lay ahead. And, in the process, money could be made from it.

While the ‘troubles’ continued north of the border, down south a travel agency, Joe Walsh Tours [JWT] was offering sun-filled holidays in far-flung and – for the time – exotic, sun-kissed locations. Money may have been in relatively short supply but good times were still the order of the day. As importantly, those times were more modern in approach and hedonistic in execution and, on television advertising campaigns, it was suggested that the Irish public ‘join the JWT set’.

In parallel, the most dominant strain of live Irish entertainment at that point, the showbands, were all but finished. As the late Paddy Cole acknowledged to his fellow musicians when witnessing a lone DJ set up his equipment in a hotel ballroom during this time: ‘that’s the end for us’.

Mohair suits were de rigueur fashion items for the newly successful and influential male elites further north of the city centre. This was especially true in the affluent suburbs of Portmarnock, Howth and Malahide. The leafy suburb of Carrick Hill in Portmarnock was home to a former boxer turned broadcaster and businessman, Eamon Andrews, who was the chairperson of the RTÉ Authority when Teilifís Eireann opened on the last day of 1961.

A member of the Bachelors, an Irish chart-topping pop act who were based primarily in the UK, resided near Andrews’s well-appointed home in a newly built modern house overlooking Howth bay. A well-known Fianna Fáil politician, Charles Haughey lived in considerable style in an opulent mansion in adjacent Kinsealy. In 1979, he began the first of four stints as Taoiseach.

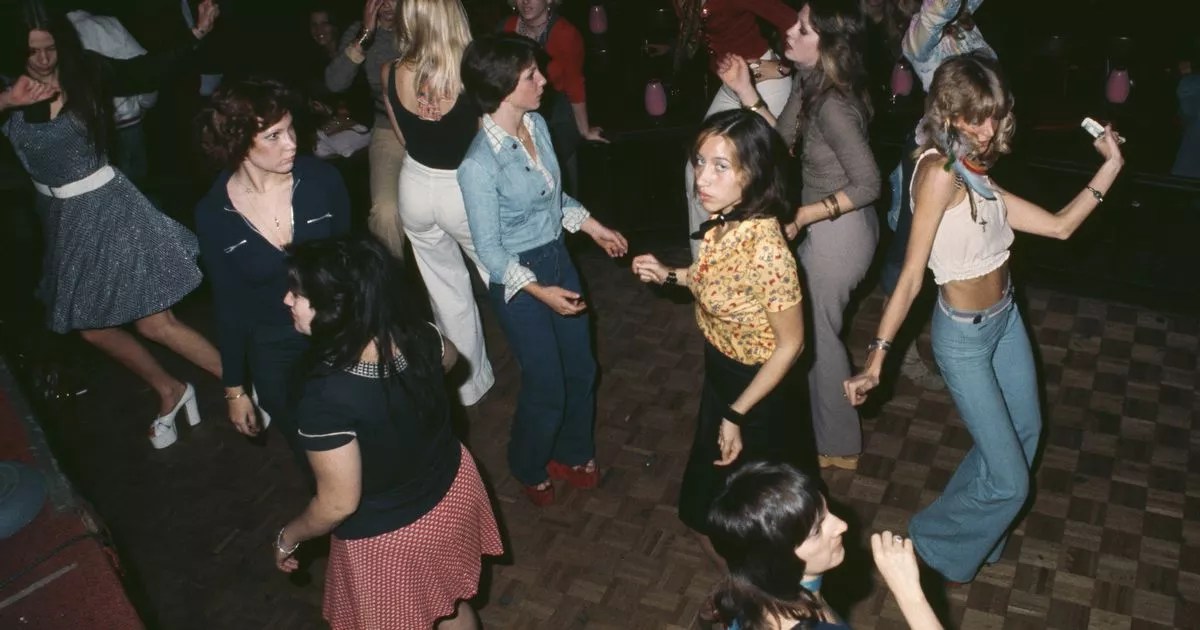

In the city centre, meanwhile, tank tops, flared bottoms, and platform shoes emerged as the leading cultural uniforms of the day. In dance music, a new upbeat form of soul took hold, a vibrant alternative to the pop/dance-floor staples of the day: offerings by Slade, T Rex, Sweet and Bay City Rollers. If rock music was a vehicle for alternative voices and pop reflected the everyday, disco spoke for the aspirational.

As well as the Lord John, other Dublin discotheques of the time – small, cramped, out-of-the-way venues like Sloopy’s which opened in D’Olier Street in 1969 and Tiffany’s, located at the rear of Roches Stores, now Debenhams, on Chapel Lane in Dublin 1 – were attracting large swathes of working people. These included fashionistas, hairdressers, would-be musicians, nurses, civil servants: people eager to be part of a vibrant alternative form of entertainment where dancing and, perhaps most importantly, glamour and the attendant sense of escapism, were central offerings.

Sloopy’s was founded by Dublin musicians Michael Ryan and Michael Murphy and is generally considered to have paved the way for the discos and club venues that emerged subsequently in the late 1970s and 1980s. [As an aside, nightclubs on the Leeson Street strip emerged during the same period but are somewhat separate and distinct entities].

To an entire generation, James Brown blasting out ‘Get Up, I Feel Like Being a Sex Machine’ on a throbbing sound system was far more preferable to Maisie McDaniels’ ‘Come Down from the Mountain Katy Daly’ drifting through the airways on Raidio Éireann.

Emerging socio-economic factors also influenced this brash form of nightlife. By the early 1970s, Dublin was increasingly attracting university students from abroad, many of whom were following medicine and engineering courses. These students were almost exclusively male and mostly the offspring of wealthy Nigerian and Libyan families.

Those from Muslim backgrounds had no interest in consuming alcohol but often dressed flamboyantly in high-end, Harlem-like fashion. This was a far cry from the dull fare for men offered at Guiney’s Department Store on Talbot Street. It’s also worth noting that the Chinese community had been the largest Minority Ethnic group in Ireland since the 1950s.

Discotheques became the natural destination for many for post-work recreation. In its own relatively minor way, it represented a flowering of sorts, an early iteration of a more multi-cultural Ireland that would take decades to fully come into bloom.

Patrons from different social, gender and racial backgrounds and groups lost themselves in the insistent, communal rhythms of what was generally a drug-free environment, enabling them to feel free – albeit often briefly – from the harsher realities of life. For others, disco was about the letting go of the mundanity of everyday working lives. This was especially true for many working-class Dubliners. So too those who felt themselves to be different, including the city’s nascent gay community.

Many young men and women had also come to Dublin to find work, lots of them looking to escape a rural, agrarian Ireland they believed held no future for them. Common to all was the need for belonging. Scores of young people from all over Ireland joined forces with young Dubliners and well-heeled international students to dance the nights away in this new world of Dubonnet, discos, and diversity: many of the discos had licence to serve wine only.

Pirate Radio had also started to emerge around Ireland, particularly in Dublin and, with rare exception, tended to focus primarily on the chart hits of the day. But the work of many of those who had become early disco staples – Betty Wright, Johnny Bristol, Millie Jackson et al – was difficult to source in most local record shops.

Select outlets like SEAL on Marlborough Street and Liam Breen’s on Parnell Street were the exceptions. On Tara Street, where the first shop in what became the Golden Discs chain opened, one or two copies of much sought-after new releases could be obtained for those desperately in need, club DJs mostly. It was a case of first come, first served. But despite what was often a paucity of material, disco’s musical imprint was being assimilated in some influential quarters of Dublin’s emerging music scene in the 1970s.

In Ringsend, a young songwriter called Paul Cleary was struck by the staccato brass arrangements and pulsating rhythm sections of acts like Tramps, Taveres and Earth, Wind, and Fire. As an emerging music agent with clients who frequented the clubs, Louis Walsh was a regular habitué of many discos. He was assembling a library that would eventually form the backbone of an early repertoire of a young boyband, Boyzone, that he’d assemble years later. Including their debut release, ‘Working My Way Back to You’, initially performed by the Detroit Spinners.

The release of the Saturday Night Fever movie and album in 1977 represented a high-water mark for the disco era, popularising the music and lifestyle worldwide. Some of the songs featured in that film are among the most enduring of the era, and the production on them is flawless. In one way, the box-office smash provided a timely and valuable critique of homophobia, sexism, and racism. John Travolta’s character, Tony Manero, escapes his bleak family life and dead-end job by dominating the dancefloor of Odyssey, the local disco. A deceptively harrowing coming of age story, it’s a dark and, at times, a seedy movie experience.

Relief comes from Travolta’s sublime dancing skills and his realisation at the film’s end that he is looking for [female] friendship, a connection that lasts far beyond the confines of the dance floor.

Undoubtedly aided by the phenomenal success and impact of Saturday Night Fever, John Ryan developed his Sackville Place basement disco into a three-story nightclub. He then opened Sands Hotel in Portmarnock, which housed the largest nightclub on Dublin’s northside, Tamango’s. Perhaps not surprisingly, he spent his final years in sunny Lanzarote, enjoying, no doubt, the fruits of his business successes.

By 1978 I had joined RTÉ as a television presenter. My first job was hosting a youth programme, Our Times, along with several others. The idea was to employ a range of rookie, would-be hosts – at least six, if memory serves – to reflect an emerging Ireland from the perspective of its youth.

The music brief on Our Times fell to me and, with producer Bil Keating’s encouragement and stewardship, we began to utilise studio resources during down-time at weekends and recorded new, young acts from around the country.

Because our endeavours came under the auspices of the Young People’s Department, we flew under the broader RTÉ radar somewhat and were left to our own devices for the most part. One of the first bands we recorded in our modest studio facility was a four-piece from Dublin’s northside called U2, in whom the bigger and most popular strands like The Late Late Show, would have had little interest.

We were allocated a three-hour Saturday afternoon slot in the cramped surrounds of Studio 2, with limited technical facilities. Given that many of the acts we worked with were, by definition, just emerging, full-on live performance just wasn’t optional. The pop promo era was in its infancy and, not surprisingly, had caught the attention of aspiring pop and rock stars.

The RTÉ canteen was a relatively quiet place to gather on most Saturday afternoons and this was where I had arranged to meet Bono, U2’s singer. The band was certainly building a following but were still largely unknown outside of Mount Temple High School, where they had formed. We were meeting to discuss what the band would like to do in the Our Times set.

I was a complete novice, still trying to understand the television recording process. Bono arrived with a jotter, complete with detailed and ambitious visual descriptions. One of the songs the band was due to perform was ‘Life on a Distant Planet’. You get the idea.

Fifteen minutes before the studio session was due to begin, I felt I needed to manage Bono’s expectations. During this first meeting, he was intense, very clearly ambitious, and eager to make the most of the opportunity his band had been given. But he was also personable, understanding and accepting of what we could achieve in the limited time we were allocated. The making of U2’s first pop promo began that afternoon, with Bono front and centre. A new era had begun, and new stories were about to be told.

By 1980, disco, as we had initially experienced it, was no more: it had become a victim of its success. But briefly, before the excesses that ultimately over-whelmed it, disco was a more than acceptable way of fleeing the everyday. And, just occasionally, an often glorious departure for a Saturday night excursion into another world.

We still live in unequal societies, of course. Silicon Valley tech billionaires have disproportionate power and seemingly unlimited – and increasingly, political – resources and influence. They tend to exhibit what can be called a paradigm blindness, a deficit of imagination to see that other people don’t always ascribe to their way of thinking.

Their mission appears to be primarily about ensuring that the elite prevail, maintaining an exclusive preserve of the few. But yet we still remain equals on the inclusive space of the dancefloor. So maybe now, more than ever, you should be dancing…

Leave a comment