Forty years ago, next month, a fire that broke out during a Valentine’s weekend disco at The Stardust nightclub in Artane, on the northside of Dublin, resulted in the deaths of 48 young women and men. As Kathy Sheridan reminded Irish Times readers in a 2006 feature piece, ‘of the 48 who died, half were aged 18 or under. All but a few were from the closely-knit, working-class, north Dublin areas of Donnycarney, Artane, Bonnybrook and Coolock’. Over 200 others in the crowd of 841 patrons that night were injured.

The dancehall and concert venue on Kilmore Road was part of a large entertainment complex that also included a public house and a restaurant, owned and operated by the Butterly family, who opened it on the site of what was formerly a jam factory, in 1978. The Stardust had quickly become a stop-off on the national cabaret circuit and hosted live shows by Gary Glitter, Joe Dolan and The Drifters, among numerous others.

In January, 1981, it staged an infamous double-bill featuring two prominent British bands of the period, The Specials and The Beat, who were in Ireland on a tour during which they also performed at The Arcadia Ballroom in Cork. The Stardust show was marred by fighting and disorder and was ended prematurely when The Specials – having pleaded several times for calm – finally had enough and walked off. More detail on the background to that concert, a fund-raiser for a children’s charity promoted by MCD Concerts, can be found on Brian McMahon’s excellent blog here.

The death in July, 2020, of Christine Keegan, who lost two daughters in the Stardust fire and who, for decades, was a prominent and eloquent campaigner on behalf of the relatives of the victims, was yet another reminder of how, for many, events in Artane forty years ago are still unresolved. A tribunal of enquiry, chaired by Mister Justice Ronan Keane, got under way in March, 1981 and an exhaustive report published later that year concluded that the ‘fire was probably caused by arson’. Although it incorporated the evidence of over 350 witnesses, some of the tribunal’s findings have long been disputed by those who survived the tragedy and by the families of those who perished in it.

The Stardust disaster has been the subject of much coverage, comment and analysis in the years since, often around key commemorative dates. A drama series that aired on RTÉ television in 2006 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the tragedy was based on Neil Fetherstonhaugh and Tony McCullagh’s fine book, ‘They Never Came Home: The Stardust Story’. While as recently as last year, The Journal, a Dublin-based on-line news service, published an excellent six-part podcast series on the events before, during and after that Valentine’s weekend, 1981. Christine Keegan, her husband, John, who died in 1986, and another of her daughters, Antoinette, who survived the 1981 fire, campaigned tirelessly and at huge personal cost on behalf of those who died at The Stardust. They, and several others, are prominent in much of the library of coverage of the tragedy, of which an RTÉ Prime Time report by Rita O’Reilly from February, 2006, produced by Michael Hughes, is still one of the most affecting and revealing pieces on the subject. What’s clear from the breadth of that archive is that Christine and John Keegan, and relatives of several of the other victims, have gone to their own graves without complete closure.

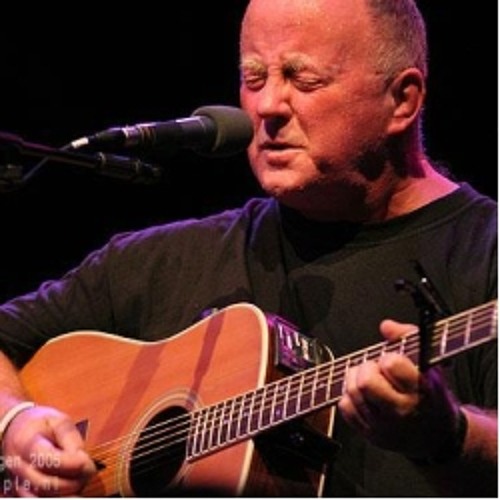

Fetherstonhaugh and McCullagh’s book, ‘They Never Came Home: The Stardust Story’, takes its title from a Christy Moore song of the same name, one of hundreds he’s performed and recorded during what is now approaching a sixty-year career in music. Moore’s own story has been very well documented, and we’re not going into the minutiae again here. Suffice to say that by the mid-1980s, the former bank official had, after what was already a diverse and colourful career, established himself as a formidable solo performer and a serious commercial draw. His 1994 elpee, ‘Christy Moore: Live at The Point’, is a fourteen song long-player assembled from recordings made during twelve one-man shows he performed at Ireland’s biggest indoor venue. One of which was memorably summed-up by the writer, Jim Carroll who, in a review in New Music Express, described the concert series as ‘one man, one guitar, one storm’. Alongside U2’s ‘The Joshua Tree’, David Gray’s ‘White Ladder’ and a record commemorating Pope John Paul II’s visit to Ireland in 1979, ‘Christy Moore; Live at The Point’ is one of the biggest-selling albums ever in the history of the state.

Moore has constantly presented as he is: a regular, unpretentious and engaging everyman with as keen an ear for a tune as for an impromptu yarn from a passer-by. But his extraordinary career runs absolutely counter to the innate ordinariness he has always projected: in the great traditions of Thalia and Melpomene, he’s as complex, vulnerable and fractured as any of those in the canon of great Irish entertainers. So that whether it’s in the delivery of his own material or his interpretation of the songs of others – and most of Moore’s best-known songs have been written by others – he’s always been a visceral live draw. For many years, a familiar image had him doused in sweat, eyes closed, head craned back, alone on stage and lost in song. ‘I’m an ordinary man, nothing special, nothing grand’, he sings on one of his best-known numbers, Peter Hames’s ‘An Ordinary Man’, in what must be one of the most self-deprecating lines in the history of popular culture here.

Like many of his primary folk influences – Guthrie, MacColl, Dylan and Seeger – Moore has also long rattled the bodhrán of social justice and, as well as the wry one-liners and colloquial couplets that pickle many of his best-known songs, just as much of his material again is determined by a sharp campaigner’s bent. ‘I don’t think anybody could talk about protest songs in Ireland without looking at Christy Moore’, Dr. Aileen Dillane, an ethnomusicologist at the University of Limerick told The Irish Examiner’s Marjorie Brennan for a feature piece in December, 2018. ‘For all his apparent localisms, he really has international reach. He connects with that Anglo-American tradition in a way that few do’. Although I’d question the extent of his ‘international reach’, Dr. Dillane’s point is certainly illustrated on Christy Moore’s 1985 single, ‘Delirium Tremens’ – a cleverly disguised iron fist of a song, one of a number of his that deal with the effects of booze – and its b-side, ‘They Never Came Home’.

‘They Never Came Home’, a Moore original about the Stardust tragedy, was originally included as the second last cut on his ‘An Ordinary Man’ album, released in July, 1985. ‘I wrote it because I try to write songs about things that affect me’, he claimed in his 2000 autobiography, ‘One Voice’. ‘I wanted to write about the Stardust because, I suppose, I felt there was a class thing involved as well’. And like much of Christy’s material, it’s a simple enough song: a mid-paced, linear ballad whose real impact is in its lyrical gut where it references ‘the mothers and fathers forever to mourn, the 48 children who never came home’.

Its two other lines elsewhere on ‘They Never Came Home’, however, that landed Moore, his record company and producer in front of The High Court in July, 1985, necessitating the recall of thousands of copies of ‘An Ordinary Man’.

Moore’s lyrics state that ‘how the fire started, sure no one can tell’. Later he sings that ‘hundreds of children are injured and maimed and all just because the fire exits were chained’. Two years previously, though, a claim for malicious damages was taken against Dublin Corporation by Scott’s Foods Limited, owners of the Stardust. After Mister Justice Seán O’Hanrahan concluded at the Dublin Circuit Court in June, 1983, that he was indeed satisfied that the Stardust fire was started maliciously, a compensation figure of £581,496 was eventually awarded to the Butterlys, owners of the Artane complex.

At the time of the release of both ‘An Ordinary Man’ and the ‘Delirium Tremens’ single, almost 240 compensation claims resulting from the Stardust fire were awaiting adjudication through the courts. With those claims still active, and following the 1983 Circuit Court decision, solicitors for the Butterly family, Scott’s Foods Ltd and Silver Swan Ltd, who had leased the entertainment complex, claimed that the two lyrical references in ‘They Never Came Home’ cited above were in contempt of court. With the first of the compensation cases imminent, it was claimed that the sentiments expressed in the song could prejudice the fairness of those hearings. An action for criminal contempt was taken by Eamonn Butterly, Silver Swan Ltd and Scott’s Foods Ltd. against Moore, his record company, WEA Records [Ireland] Ltd – through its managing director, Clive Hudson – Aigle Studios, where the record was produced, through its owner, Nicky Ryan, and the album’s producer, Donal Lunny.

That claim was up-held by Mister Justice Frank Murphy when the action was heard in The High Court in Dublin on August 9th, 1985. But he also concluded that the song wasn’t written with the intention of obstructing or interfering with the process of justice and that it wasn’t a case in which it was necessary to impose punishment or sanction. As an aside, Christy Moore was defended in court by Sean MacBride, S.C., a son of Maud Gonne and the founder of Clann na Poblachta, a former government minister, Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army and, latterly a Nobel Prize Winner.

At the time of the hearing, ‘An Ordinary Man’ was the best-selling album in the country and ‘Delirium Tremens’ was a Top Ten single: an estimated 12,000 copies of the album had been distributed to various outlets around Ireland. Following Judge Murphy’s ruling, the song could no longer be promoted, sold or dispensed in Irish record shops. Nor could the song be played on radio. ‘They Never Came Home’ had, to all intents, been banned.

Christy Moore, by his own admission, was ‘scared’ about the High Court action but his primary concern, unsurprisingly, was for the families of the victims of the Stardust fire and for the many survivors, none of whom he wanted to re-traumatise. He needn’t have worried: the court-room was packed on the day of the hearing, with many of the families fetching up in support of the singer. Subsequent to Judge Murphy’s ruling, thousands of copies of ‘An Ordinary Man’ and ‘Delirium Tremens’ were recalled and destroyed by WEA. ‘They Never Came Home’ was eventually replaced on the album by a fresh cut, ‘Another Song is Born’, written by Moore and recorded by Nicky Ryan in his home studio in Artane, of all places. Fetherstonhaugh and McCullagh claim in their book that ‘the whole episode cost Christy Moore, his manager, Mattie Fox, and the record company in the region of £100,000’.

Four Dublin record shops, including Golden Discs, were back in front of Justice Murphy the following month when it was claimed that, despite assurances given by WEA, original copies of ‘An Ordinary Man’, featuring ‘They Never Came Home’, were still available on the racks. The shops were ordered to remove them. Unsurprisingly, ‘They Never Came Home’ quickly became a cause celebre and, for a while, the original version of ‘An Ordinary Man’ was a rarity of sorts: its freely available now, at standard cost, on the usual on-line sites.

Christy Moore was among the huge crowd that gathered at the Church of Saint Joseph the Worker in Bonnybrook, during Christmas week, 1986, for John Keegan’s funeral mass. He performed an older song, ‘John of Dream’, during the service, a number that first appeared on a 1980 compilation album from Tara Records and that was added subsequently to a re-issue of his ‘The Iron Behind the Velvet’ elpee. He performed ‘They Never Came Home’ at the official opening of the Stardust Memorial Park in Coolock in 1993, and a live version was included on a box set of Christy Moore material, issued in 2004 to celebrate what was then the 40th anniversary of his career in music. He also chose to perform the song during two Late Late Show appearances over the last decade.

Meanwhile, the Stardust story refuses to go away. In September, 2019, the then Attorney General, Seamus Woulfe, ordered a fresh inquest into the 48 deaths in Artane on Valentine’s weekend, 1981. It’s hoped that the initial phase of this process will be concluded before the end of 2021.

Excellent piece Colm

LikeLike

Have only come across this article just now. The new inquest is FINALLY underway. I’ve only one word to add – SUPERB👏👏!

LikeLike

Many thanks for reading and for posting, Marian. We really appreciate it. Thank you. Colm

LikeLike